I have two friends that always leave me feeling somewhat better after I speak with them. One is always on some cool project that stimulates my intellect so our conversations are great. I call the other one to complain about issues I have every now and then and hear his as well.

When this second guy tells me about his concerns, his debts, his personal struggles, no matter how worried I feel about my situation, I always finish the conversation feeling like “Wow Maxwell you have it not as bad as you think, AT ALL!”.

That is how refugees make me feel when I speak with them. They make me feel like Ghana’s cherished democracy and affinity for peace and calm should not be undervalued in the slightest bit.

My network provider frustrates me so much when I get interrupted cell service (I am not naming anyone oo). Traffic on the relatively short route to my house after work can keep me in a foul mood for taking two hours I could have deployed doing something else. After I speak with Rya Kuewor and Avina Ajith, that day, I whistle on my way home.

Why?

Because I feel lucky to have my life as it currently stands. Also, read the title to this article again: Crypto-driven Universal Basic Income as a tool to reach refugees during the pandemic. What a title! These are the guys behind such an initiative.

Look at all the havoc COVID-19 is wreaking with its line-up of variant after variant. I just read about a new Delta-plus variant and I haven’t even fully understood the Delta variant yet. If you find yourself in a refugee camp, you can just imagine how quickly things can get dire.

As noted by the Global Spokesperson for the UNHCR, “Discriminatory restrictions on access to health and social services and a dramatic loss of livelihoods is driving many refugees and others on the margins of society deeper into poverty and destitution.”

Also reported in Ghana, “Refugees and migrants were left more vulnerable with limited protection and rights, facing inequitable distribution of even masks and soap, ostensibly existing refugee aid and support weren’t sufficient in dealing with a global pandemic.”

Refugees have had it badly long before this deadly global pandemic reared its ugly head, which raises the question: how can we relieve the extreme duress on certain communities around the world struggling to cope with the impacts of COVID-19?

The public has the tendency to always point to what should have been done. Spend a cedi here and you’d hear how you should have spent it there. Spend a cedi there the next time and you’d here how something way over there needs more attention. Let’s not do this with this subject matter. Let’s concentrate.

Refugees leave their countries for various reasons, mostly seeking refuge, as the name suggests. You’d cherish your access to education when you hear how without the limited scholarship and donor programs available to them, a significant number of refugees have to stop schooling after junior high, that’s even if they get there. One man came to Ghana from Liberia in a canoe, after losing his entire family to gruesome war crimes.

Let that sink in: he came not in a boat, not in a ship, but a canoe, from the shores of faraway Liberia, to Ghana’s shores, by sea, amidst all the storms and tidal turbulence, in a handmade wooden canoe. Anything could have happened. And he came here with nothing, lucky to have his life and a chance at another shot at living.

If a group of young migrant integration consultants have figured out a way to impact these refugees, and in a big way, then it’s worth mentioning. Even with just $1.50 a day to a refugee as Universal Basic Income (UBI), utilising cryptocurrency and other innovative ways of disbursement, it can mean everything and anything from food for an entire household to much needed basic medicine. Rya and Avina impact tens of thousands of refugees through the Refugee Integration Organisation (RIO). Please find information on work that’s being done below, by kind courtesy of RIO.

RIO and partners find a way past the exclusionary modernity of technology to bring blockchain-driven UBI to underprivileged refugee communities.

With the accelerated advent of the Fourth Industrial Revolution, it has become ever more easy to deploy new cutting-edge technologies in existing and worsening vulnerable communities. But innovations in new tech do not necessarily translate into working solutions. Sometimes, tech needs to be dialled back in order to reach the most vulnerable in communities and have the most effective outcomes.

The Refugee Integration Organisation (RIO) did just that by taking a cryptocurrency (Celo Dollar) based UBI programme by Impact Market — which distributes money through mobile apps — and incorporating a USSD feature linked to beneficiary mobile money wallets, so even refugees without smartphones or those who aren’t tech savvy could receive these vital funds. In short, unaccompanied minors, the elderly, the ill etc., can all access these funds without any special training.

In thinking through solutions, we ask ourselves — are practical economic development interventions in refugee camps truly as difficult to achieve as they appear? The answer, for us, is “No”. RIO displays great scope by scaling down technologies, creating the right partnerships, and skilfully shifting power-of-management to the residents of refugee camps.

Resistance to UBI is founded upon people’s visceral response to unconditional hand-outs, forgetting that the hand-out is only enough (if even) to support subsistence and bare survival. Critics often fear outcomes of induced lethargy, loss of productivity and moral hazards. They believe UBI could have a negative domino effect on economies by reducing people’s incentive to work (or inducing a disincentive effect on the workforce) and driving up wage rates.

However, a World Bank report and empirical research across contexts has shown no negative effects on labour force participation and enhancements in productivity. In fact, a study on a Namibian UBI experiment called BIG shows that the programme encourages people to pursue more income-generating activities, thus producing positive spill-over effects for the local economy.

In 2019, RIO tested microfinance paired with entrepreneurship in the Krisan Refugee Camp, Ghana. Beneficiaries succeeded in establishing small businesses within the camp, resulting in a 97% repayment rate. With three new home-cooked food enterprises, a hair salon, and an essential goods shop, all within the camp, the exciting part was yet to come.

The real test was whether it could be managed in the long term by the refugees themselves. And for months leading up to the pandemic, it could! Sales were high, and profits were helping not only their households but the community at large. While the entrepreneurs did their best to keep their new businesses afloat, the pandemic and repeated lockdowns made essential items inaccessible for refugees, even for daily sustenance.

In 2020, RIO came back to Krisan Refugee Camp to remotely pilot an Unconditional Basic Income programme, now providing 700 residents with $1.5 a day. Instantly, we saw businesses and opportunities crop back up, including some of the small-enterprises from our previous programme. Residents report that the daily funds brought relief to severe cases of hunger, lack of access to medicine, lack of sanitary and hygiene products, and lack of access to communication through mobile data or calls.

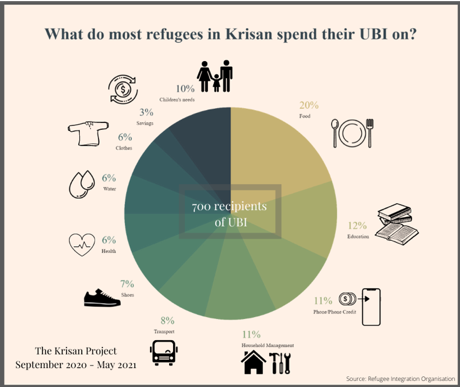

RIO’s preliminary data on how UBI has alleviated some of the devastation from the pandemic shows that not only were the residents of Krisan using their UBI to purchase vital sanitary products, medicines and food, but they are also investing in small businesses or trades, some of which run using just WhatsApp groups and the Celo currency. Other instances of UBI being an instrument of enablement includes a Sierra Leonean couple saving the daily funds to build the first modernised hair salon at the Krisan camp. Another shows a young gentleman, who was born at the camp, using his UBI for driving classes and a license. These accounts are only a couple of several. The chart here illustrates some early data from another study on what some recipients primarily spend their UBI on.

On a more ethical note, UBI hands agency back to the recipient. What they choose to do with the money is entirely their prerogative, which in a way is a means to destabilise the power structures that hold vulnerable populations hostage to inefficient policy implementation. It enables the individual to make decisions for themselves and actively create the future they hope for, thereby reinvigorating a sense of hope and dignity. In the medium and long term, we observe that micro economies emerge and essential needs can now also be catered for by resident refugees themselves.

Also emerging is proof of efficient self-management of this UBI model. Seven months into our UBI pilot, with a capacity of managing 15,000 beneficiaries, we are funding four communities in Ghana, Kenya and India with just five remote managers. The managers help set it up, but all other matters, including onboarding, troubleshooting and distribution of funds are in the hands of trained residents from the community. This in the very least proves that organisations can also save funds spent on providing external staff to manage economic development programmes and greatly reduce the risk of fraud — overseeing from a distance may very well suffice.

It would seem the larger the sample space, the more complex a system such as this would get, but hasn’t proven to be the case for RIO. Kakuma Refugee Camp in Kenya had a population of 196,666 at the end of 2020, when RIO partnered with Kotani Pay to pilot their pioneered, scaled down model of blockchain technology in Kakuma, which enabled non-smartphone users to claim UBI in the form of cryptocurrency. And since this tech is majorly automated and made accessible through any mobile device, the Kakuma program has been run entirely by the refugees themselves. At the current rate of onboarding 1500 people a month, management costs are minimal because upkeep is low, which broadens the horizon of opportunity for refugees all over the world.

Let us conclude with the following ideas for your consideration: if some citizens require this basic income to help keep off poverty lines, how much more do refugees, migrants, and other Persons of Concern? Also, is it time to reimagine technologies in vulnerable and underprivileged communities? Do we need to scale down modern tech to fit unique needs? At this juncture, it is important to acknowledge that large portions of our world have not yet caught up to all the technologies of our time and it is imperative that solutions be tempered accordingly.

[1] Haarmann, C., Haarmann, D., Jauch, H., Shindondola-Mote, H., Nattrass, N., van Niekerk, I., & Samson, M. (2009). Making the difference! The BIG in Namibia. Friedrich Ebert Foundation.

I hope you found this article insightful and enjoyable. Subscribe to the ‘Entrepreneur In You’ newsletter here: https://lnkd.in/d-hgCVPy.

I wish you a highly productive and successful week ahead!

♕ —- ♕ —- ♕ —- ♕ —- ♕

Disclaimer: The views, thoughts, and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author, Dr. Maxwell Ampong, and do not necessarily reflect the official policy, position, or beliefs of Maxwell Investments Group or any of its affiliates. Any references to policy or regulation reflect the author’s interpretation and are not intended to represent the formal stance of Maxwell Investments Group. This content is provided for informational purposes only and does not constitute legal, financial, or investment advice. Readers should seek independent advice before making any decisions based on this material. Maxwell Investments Group assumes no responsibility or liability for any errors or omissions in the content or for any actions taken based on the information provided.