Coronavirus cannot be Defeated for any of us until it is Defeated for all.

The coronavirus has over time proven to not only be a health pandemic, but also a potentially devasting economic catastrophe to billions worldwide. It is the society’s weakest and poorest that are likely to be worst hit.

It’s not far-fetched to say that no economy is exempt from the negative impact of another. It’s a global village after all, as advertised. Thus, current times make it stupendously ill-advised to leave Africa’s economy out of conversations on reducing the fiscal impact of COVID-19 now and after we beat it, specifically the threat to the poor and needy.

It is no longer a secret that should this coronavirus continue to spread into the coming months, for the poorest of us, the plunge from prosperity to peril will be as swift as the switch to lockdown protocols. The 2020 economic growth rate for the world and that of individual countries have already declined to very low values, implying no improvement in standards and cost of living for those that are already at the bottom of the barrel.

That is focus of what you’re about to read, a spotlight on those at the bottom of the barrel and how this pandemic will likely mean much worse for them.

Rya Kuewor is the Co-Founder and Executive Director of the Refugee Integration Organization (RIO) and an Agenda Contributor with the World Economic Forum. Simon Turner is a Consultant with the African Health Innovation Center and a Director at Founder Institute. Both are Migrant Reintegration Consultants with SOCIAL IMPACT, an organization that has been instrumental in designing and implementing innovative qualifications and start-up support for socially disadvantaged groups.

These are all facts, and this is an opinion piece.

Enjoy the read!

♕ —- ♕ —- ♕ —- ♕ —- ♕ —- ♕ —- ♕ —- ♕ —- ♕

By Rya Kuewor and Simon Turner

While it is fair to say that to some extent COVID-19 doesn’t discriminate, it’s also a given that once it starts to hit the world’s poorest, marginalised and most vulnerable, inequality will yet again prove to be a devastating curse.

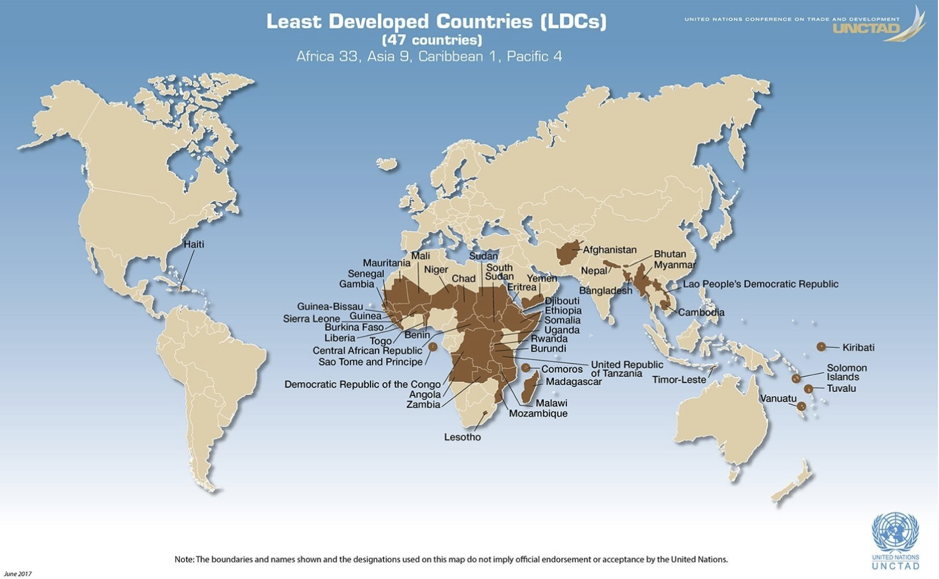

With little or no access to clean water, shelter, information, healthcare, food, or even the luxury of “social distancing”, the world’s poorest and most vulnerable are at increased risk of suffering the worst from COVID-19. Adding up the 25.9 million refugees living in camps, and the 41.3 million Internally Displaced People (IDPs), as well as the 900 million people who live in the Least Developed Countries (LDCs) – most of which are African nations – over a billion people are at risk and almost 50 countries face the risk of catastrophic failures.

The Problem

While recognising the importance of learning from other countries like China, Italy, Germany, and South Korea, African leadership and its citizens should not think Africa, as sovereign nations and as a continent, will experience similar timeframes with regards to the time it will take to get a handle on the extent of COVID-19 pandemic. As of today (10 Apr, 2020), there are just over 13,000 recorded cases in the whole of Africa, but celebrating these relatively low numbers as a win would be a mistake, because they are at least partly a result of insufficient testing.

We are also potentially being lulled into a false sense of security by taking as gospel the possibility that the disease is less infective in warmer temperatures. Even if it were the case, “this will be a source of concern for Southern Africa, which is heading into its colder months and “flu season,” and so their healthcare systems – already creaking – will quickly be overwhelmed. The outlook for the rest of the continent is equally bleak, with most countries unprepared to cope with the pandemic for a prolonged time. This coping ability is contingent on how soon robust measures to combat the viral spread are enforced and/or a vaccine or other solution is developed (which is unlikely until before 2021), but most African nations currently cannot effectively implement these measures.

The Impact

The public health, economic and social devastation the world has seen in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic will be many times more severe in developing countries if the viral spread is not contained. In normal times, low-income countries are familiar with poor infrastructure, social amenities and healthcare (not to mention conflict) – with Africa alone carrying a quarter of the world’s disease burden but is responsible for only 1% of global health expenditure – meaning that adding on the ravages of COVID-19 further worsens the situation of many African nations.

Africa quite simply is unlikely to be able to follow most of the world in locking down countries and regions to help contain the spread of the Coronavirus. While the US, European, Australasian and Asian countries are able to enforce quarantines, they can also cushion the impacts of the quarantines on their citizens. From direct financial aid to households, to corporate bailouts of up to 2 trillion dollars (in the US), these nations and regions are far better prepared to deal with the pandemic and its immediate aftermath.

About 85% of Africans live on less than $5.50 dollars a day, many earning daily wages in low-skilled work. Enforced quarantines and stay-at-home orders will abruptly upend the livelihoods of these people, many of whom do not have the reserve resources to shelter in place. For the people who live hand-to-mouth and in extreme poverty in Africa, many living in shacks and slums with little chance of social distancing, insufficient potable water or sanitation, their communities could easily become a nexus for the viral spread. Because more than a quarter of the world’s hungry live in Africa, the imminent dilemma of either starving or maybe catching COVID-19 will become a bleak reality for many poor families, some of whom may be forced to risk infection.

For some of these vulnerable communities, particularly in refugee camps and for many IDPs, the threat of pandemic is but another of many life-threatening situations they have had to navigate for years. In addition, following how Ebola caused grave stigma against survivors, COVID-19 may engender how survivors or infected persons are treated. Facing the potential for vigilante violence, some already marginalised infected people may decide not to get tested or receive treatment.

The expected economic impact of COVID-19 in Africa is another formidable battle in its right. Carrying over $100 billion in sovereign debts, African governments will be hard-pressed to meet their debt obligations, serviced at up to 10% – mostly because of their reputation as risky borrowers. Amid sudden disruptions to international supply chains and reduced foreign direct investment and demand for raw materials, African economies are projected to grow 1.8% in 2020, almost one half of the 3.2% growth rate forecasted before the pandemic. Additionally burdened with necessary quarantine measures like closed borders and reduced internal trade, these governments will see their already insufficient internal revenues shrink dramatically.

African governments and organisations are mitigating the crisis, and have enacted economic stimulus spending plans to help soften the blow of COVID-19, like the African Development Bank’s $3 billion bond for economic relief in African countries. Also countries like Ghana, Kenya, Morocco, Egypt and Mauritius have rolled out stimulus packages, and cut interest rates in response to the crisis. The question now remains of how much of this economic alleviation will reach the most vulnerable people – who are least able to weather this crisis, and how much of it will be corporate handouts.

The success of African governments’ efforts in managing the COVID-19 pandemic is partly contingent on their economic relationship between its trade and economic partners, such as China, Europe and the IMF. Without debt relief, bailouts and humanitarian aid, many African economies could crumble under the weight of the pandemic effects. Granted, many indebted African governments were overleveraged before the crisis, but those issues could take a backseat in the interim – you don’t focus on the firefighting bill while the house is still on fire. It is imperative that multilateral institutions like the IMF and World Bank Group support African economies, and give them the fiscal space they need to survive this crisis, as well as get back on their feet when this is over.

The Hope

In dealing with the public health, social and economic devastation of COVID-19, countries have adopted different approaches to dealing with the crisis, including technological tools that have immensely enabled developed nations to implement quarantines without total disruption. Even though developing countries have limited access to some of these tools and the infrastructure they require, many of them, such as Ghana, have taken heed of the early warnings and learned lessons from earlier affected countries.

The urgency of the crisis has spurred some good innovation across Africa, like Senegal’s race to mass produce cheap test kits. In Ghana, Redbird Inc., a healthcare startup has developed a Covid-19 Symptom Tracker and Reporter to help public health officials map the geographic spread of symptoms. As Patrick Beattie, the CEO of Redbird states, “necessity is the mother of invention and it means it’s even more important for us to develop new tools to help those in charge of the response.”

Between these public health efforts and different measures to soften the economic blow of this pandemic, developing countries are bracing themselves to get hard-hit by COVID-19. The extent of this anticipated damage is still unknown, and so it is anyone’s guess how well countries will survive this crisis. One of the few things we do know, however, is that “supporting the poorest countries is essential because this crisis cannot be defeated for any of us until it is defeated for all.”

I hope you found this article insightful and enjoyable. Subscribe to the ‘Entrepreneur In You’ newsletter here: https://lnkd.in/d-hgCVPy.

I wish you a highly productive and successful week ahead!

♕ —- ♕ —- ♕ —- ♕ —- ♕

Disclaimer: The views, thoughts, and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author, Dr. Maxwell Ampong, and do not necessarily reflect the official policy, position, or beliefs of Maxwell Investments Group or any of its affiliates. Any references to policy or regulation reflect the author’s interpretation and are not intended to represent the formal stance of Maxwell Investments Group. This content is provided for informational purposes only and does not constitute legal, financial, or investment advice. Readers should seek independent advice before making any decisions based on this material. Maxwell Investments Group assumes no responsibility or liability for any errors or omissions in the content or for any actions taken based on the information provided.